When you get pregnant, besides the fear of miscarriage, the fear of having a child with a disability is perhaps the biggest fear you have. It certainly was for David and I. How do you take care of a special needs child? What will your life be like? It was uncomfortable to think about. And it was scary, not because the child was scary, but because the whole process was incredibly unknown. We were afraid because of our own ignorance. I would think we are not alone when it comes to this fear. And it’s not something that most people talk about. It’s kind of embarrassing to admit you’re afraid of a situation like that, isn’t it?

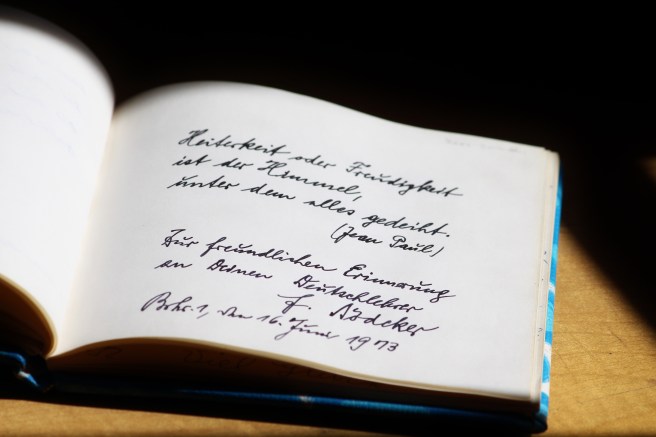

Yesterday, as David and I were leaving Dekalb the head NICU nurse (correction: I was misinformed, she is not the head NICU nurse lol) shared with us a very personal and beautiful story as well as this poem, “Welcome to Holland.” As she told me about the poem, I thought that it could not be truer. Our perspective on special children is completely different now that David and I have a severely special needs daughter.

Whereas before it was something to fear, now it is nothing. She’s our daughter, we don’t see anything strange or different about her. She’s just Brielle. The fear of all the work involved with her doesn’t seem like work anymore. It just feels normal. I’m her Mom, if she needs me to clean an open brain dressing, then I will change her dressing. If she needs me to give her supplemental oxygen, then I will give her supplemental oxygen. It’s not so scary.

Love doesn’t work that way. Love doesn’t say, “I can only do this much, but I can’t go any farther than that.” Love doesn’t have limits. And if loving my daughter means that I have to hold her and help her pass peacefully and comfortably, then I will hold her, and tell her it’s okay. I will put on my best face and surround her with as much love as I can.

David and I don’t feel as if we were punished or burdened with a child that is different. If anything we feel blessed. Before we had her diagnosis I was thinking about how I would teach my children french and english. Having a child that is different puts everything in perspective. Sure it would be nice if my children were bilingual, it’s wonderful that we have doctors, rocket scientists, straight A students. But if the only thing my daughter ever does is smile or move her little arms, well, that really is enough.

And really it comes down to, is my child happy? Is my child loved? Yes? Then I have done my job as a mother. There’s so much that the world tells us we need to do to make our kids succeed or do in life. And maybe you’ll disagree with me on this, but those things don’t matter. Life is too short and we really have no idea how long we have with each other.

Brielle’s life, a special needs child’s life, is full of love and innocence. What is better than that? I told David last night, if we have another special child, it’s okay. I’m okay with it. I don’t want to lose another child, but if I get the opportunity to shower another child in love and be equally loved in return, I can do that. She’s such a happy baby, what is there to complain about or be sad about? Holland is just as wonderful as Italy.